Saskatoon – When developing a new concept or process, finding its flaws sooner than later is a key concept, and one that the Saskatchewan Research Council (SRC) takes to heart.

Mike Crabtree is the Saskatchewan Research Council’s vice president for their energy division. He’s based in Saskatoon. He spoke to Pipeline News on Jan. 15 about the organization’s broad efforts.

“SRC has a number of industrial divisions that represent, reflect and match the resource industries of Saskatchewan. So we have a mining and minerals division that looks at everything from potash through uranium, diamonds, gold and rare earths, looking at research and developmentand commercialization in those areas, working with the major mining companies in Saskatchewan and beyond.

“We have an environmental and ag-bio division that looks at everything from air quality monitoring, right through to plant genomics.

“Then we have my division, the energy division, and our responsibilities look at everything from bitumen to Bakken. We look at bitumen enhanced oil recovery, looking at new SAGD (steam assisted gravity drainage) techniques right through to looking at light and tight shale gas and shale oil. Alberta and Saskatchewan have those full range of products.

“The Saskatchewan Research Council, as the name implies, is heavily focused on Saskatchewan, but we have clients across Canada. We have many of clients across Canada, and some 1,500 clients across the world,” Crabtree said. “We’re an international research and development and commercialization facility.”

They have annual revenue in the range of $70 to $80 million and have in the region of about 360 employees. “The majority of those employees are scientists, engineers and technicians, so we’ve very heavily technically focused,” he said.

There are about 40 people in the energy division, largely based in Regina,

“We work on enhanced oil recovery, from light oil to bitumen, everything from sub-surface enhanced oil recovery through completion issues to surface production problems,” he said. They also have a pipe flow unit in Saskatoon, which has pipe test loops ranging from 1 inch to 20 inches in pipe diameter, capable of testing pipeline flow regimes at real commercial scale.

“We work in some cases, on joint industry projects with a number of operators, funded sometimes by government, both federally and provincially. Common issues are around the development of new EOR techniques, through to new pipeline technologies and testing them, right through to highly-confidential bilateral work with oil and gas operators,” Crabtree said.

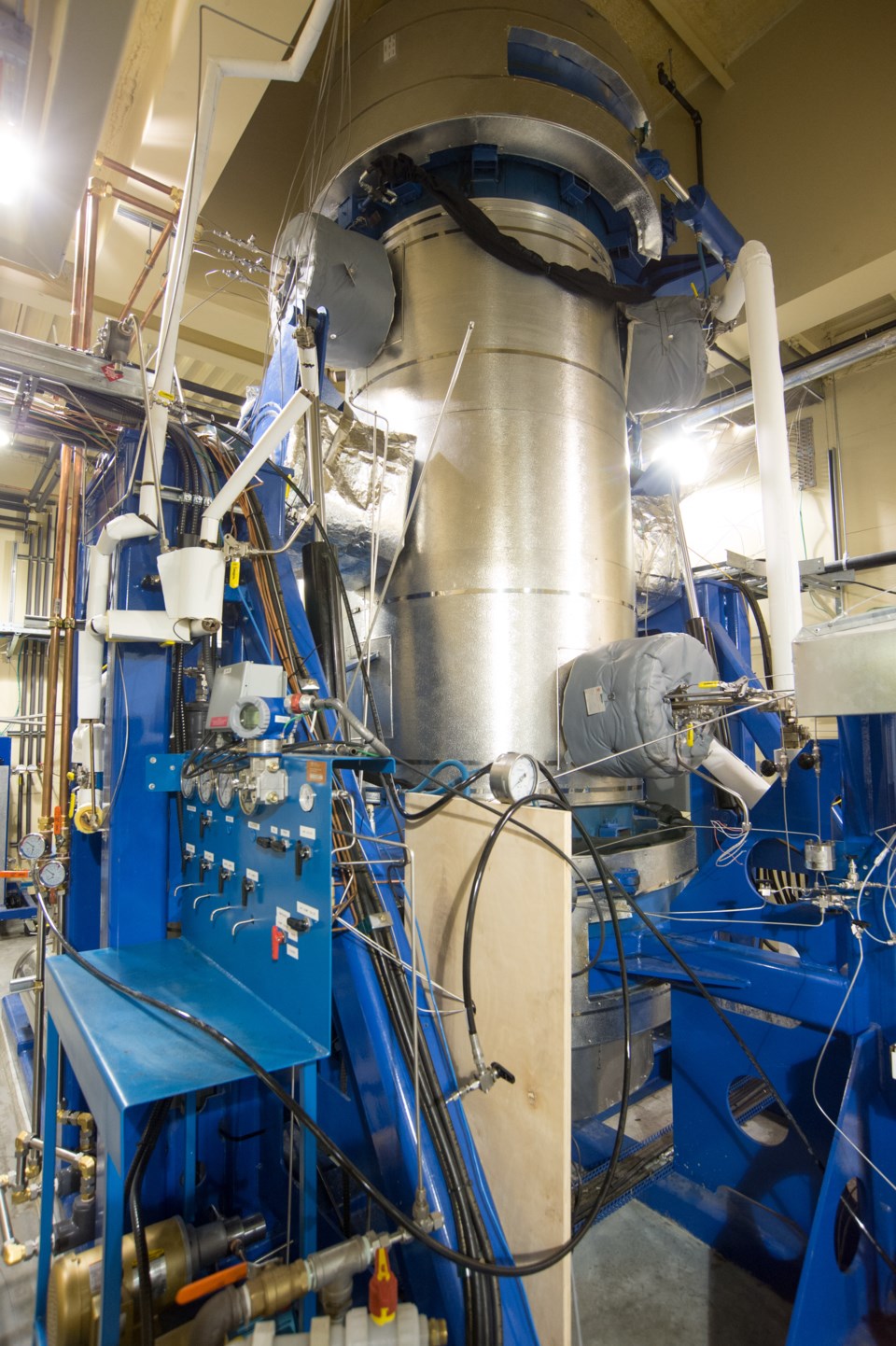

In Regina they have numerous laboratories and testing apparatus. One is a large-scale three-dimensional reservoir testing simulator, the TSVX. It looks something like a giant R2-D2.

“A lot of organizations, public and private, focus on small-scale experiments, maybe one-inch diameter and maybe a foot long. We do that work, absolutely, but can scale up to those very large vessels.

“For example, a core flood an inch in diameter and 12 inches long is a million times in scale away from a small reservoir. By the time we get to the large simulator, we’re 1,000 times away from the reservoir. So that scale-up is a lot of de-risking and comfort for the operators. If they test a new process, at that scale, they’ve got a lot more comfort that it’s going to be able to work at field scale. So that’s a lot of our work, in the scale-up of technologies,” Crabtree said.

Developing “early stage” ideas into proof of concepts that are actually going to work is key.

The technology readiness level (TRL) scale describes where a technology is between its concept and its readiness for commercialization. Crabtree said, “TRL 1 is where somebody’s come up with a concept. They’ve done perhaps an engineering study and they say if we put this together with this, under these conditions, it could significantly improve the process. But it’s totally unproven. It’s a concept.

“And you move through a quite-rigorous testing and validation regime, when you get toward TRL 8 and 9, where it’s piloted and ready for commercial uptake. What we do, as a research and development laboratory, is work with our clients to take it through that technology readiness scale.”

He went on, “The other thing we work on is stage-gated fast-to-fail.

“If you’re going to fail with this concept, you want to fail fast, and you want to fail early. Why? Because that’s going to cost you the least amount of money to get to that important information that it’s not going to work. Also, it often allows you to cycle back and improve the failure mechanism at an early stage. It also keeps the cost down.”

As an example, two years of early testing might cost the operator between $50,000 and $100,000. If that is successful, scaling it up might cost $200,000, totalling a $300,000 investment. “Wouldn’t you rather know it’s not going to work when you’ve spent $100,000 than when you’ve spent $300,000?” he posed.

By the time you’re testing something in the TSVX vessel, each two-month run might cost between $150,000 and $200,000. “You don’t want to find, at that stage, that some fundamental part of the process is failing. You want to find it when you were spending $100,000 on a test. So that’s what we call stage-gated fast-to-fail, and it’s a very important process in everything, whether it’s in pipe flow, or if we’re looking for a subsurface enhanced recovery process.”