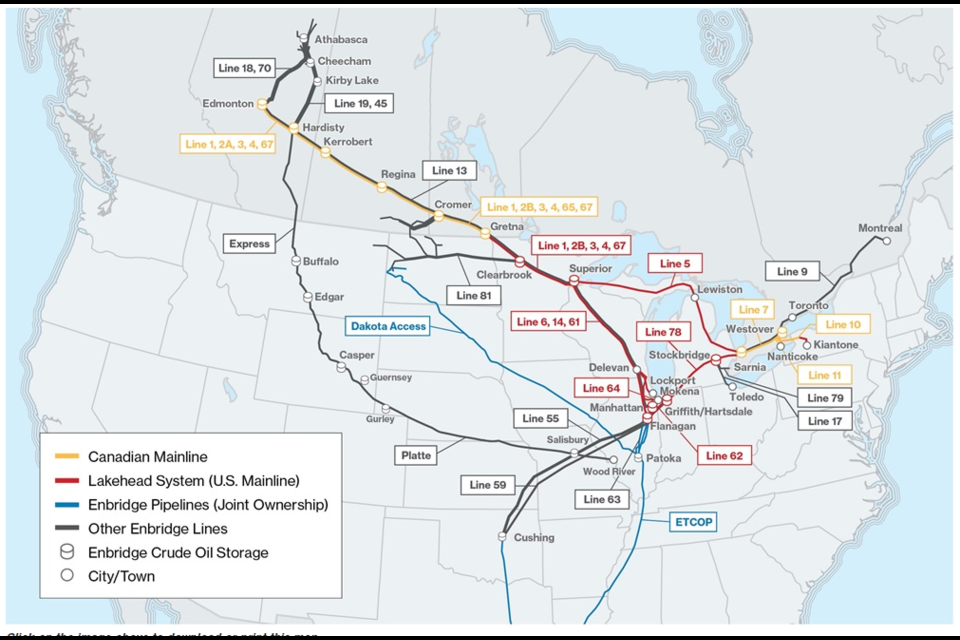

April 30 marks the 70th anniversary of Enbridge’s Mainline system, which traverses Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba and is Canada’s largest crude oil transportation network.This sophisticated pipeline infrastructure safely carries a variety of crude oil types, including production from the Canadian oil sands, to refineries across North America. Here’s a look at how this integral pipeline network, and Enbridge Pipelines, came to be . (Submitted by Enbridge)

Saturday, April 30, 1949, was the last sitting of the Canadian Parliament before members went home to begin campaigning for a June election. Amid the dozens of bills receiving final approval and royal assent that day, two were of crucial importance for the company that would eventually become a key part of Enbridge. The Pipe Lines Act established federal regulation of interprovincial and international pipelines, and it provided that liquids pipelines could serve as common carriers like railways, open to multiple shippers. The Interprovincial Pipe Line Act incorporated IPL as an independent entity with its own board of directors and the ability to raise capital, build facilities, and manage pipeline operations.

Parliament thus ended the first chapter in a story that began shortly after the major oil discovery at Leduc, Alberta, in February 1947, and it opened the second chapter leading to the arrival of crude oil in Superior, Wisconsin, in December 1950. These events unfolded very rapidly—astonishing compared to today’s processes—and reflected the “can-do” determination and ingenuity of that era.

Imperial Oil and its 69 per cent shareholder, Standard Oil of New Jersey, played leading roles in IPL’s creation as they scrambled to get Alberta’s new oil glut to markets. In the immediate aftermath of the Leduc discovery, they dug up a 60-year-old pipeline in Ohio and used it to carry the oil to railway connections in Edmonton. A refinery in Whitehorse, Yukon (part of the wartime CANOL project) was dismantled and transported to Edmonton, where it began operation in July 1948. Severe post-war steel shortages dictated these decisions. Imperial sold its large South American subsidiary, International Petroleum, in March 1948 for $80 million ($911.8 million in today’s dollars) to finance Canadian oil field and pipeline developments.

Most of the Leduc area crude was sent initially by rail to refineries in Regina. Imperial calculated that a pipeline to Regina would reduce the shipping cost from $1 per barrel to about 25 cents. The company’s board approved building a 450-mile pipeline in May 1948. The planned western terminus was moved from Nisku to its present location in eastern Edmonton after discovery of the prolific Redwater field north of the city in August 1948. Bud Speaker and Mark Connolly, later IPL district superintendents, made a preliminary survey of the route to Regina that summer. An engineering group assembled in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in November to begin the detailed planning with the assistance of Standard’s Interstate Pipeline subsidiary.

In December 1948, Imperial ordered 450 miles of 16-inch pipe from a mill in Welland, Ontario; this was the largest diameter that could then be produced in Canada. When a longer system was later approved and larger sizes became available from U.S. suppliers, 20-inch pipe was used between Edmonton and Regina; the Canadian 16-inch pipe was laid between Regina and the U.S. border at Gretna, Manitoba, and 18-inch pipe went from there to Superior.

Oliver Hopkins, a senior vice president of Imperial who would become IPL’s first president, had been gathering an executive team in Toronto since 1947. They faced continual challenges as Alberta discoveries kept increasing the potential production and expanding the potential markets. The first proposal, extending the pipeline to Winnipeg, would have been relatively simple and affordable. The much larger volumes available after Redwater raised the ante considerably in the final months of 1948.

The United States was amply supplied with its own crude oil in the 1940s and in fact supplied much of the Canadian refinery market. Major import routes included Imperial’s Cygnet Pipeline built in 1913 from Ohio oilfields to Sarnia; a pipeline from Portland, Maine, to Montreal built in the early 1940s to reduce tankers’ exposure to German U-boats off Eastern Canada; tanker deliveries to Vancouver and Halifax, and rail shipments to the Prairies. The pipeline planners in Toronto and Tulsa realized that the next logical market for Alberta crude after Winnipeg would be Sarnia, Canada’s largest refining and petrochemical centre, which could be reached by tanker from Lake Superior. Getting to a lake port added cost and complexity and necessitated delicate negotiations with governments.

Hopkins and attorney Bob Burgess, who would become IPL’s general counsel, won crucial support from Canadian Trade Minister C.D. Howe, known as the “Minister of Everything,” mainly because the project would provide a big boost to the nation’s balance of payments. However, Howe was also the Member of Parliament for Port Arthur (merged with sister city Fort William in 1970 to become the city of Thunder Bay), and he preferred an all-Canadian route to the Great Lakes. The Imperial team eventually convinced him that the longer distance and difficult terrain of the Canadian Shield would add $10 million to the cost and delay completion by a year. The government began drafting the necessary pipeline legislation, and Imperial petitioned for a bill incorporating IPL. Talks also began with U.S. authorities on permits for a pipeline across Minnesota to a port at Superior, Wisconsin.

Canada had no previous federal pipelines law, so the Pipe Lines Act was closely modelled on the Railways Act; it gave regulatory authority to the Board of Transport Commissioners and included key provisions such as the right to expropriate right-of-way if necessary. The bill received little notice amid the other momentous political events that winter: Louis St. Laurent replacing Mackenzie King as prime minister, Canada joining the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, and Newfoundland joining Confederation, among others. The pipelines legislation was not introduced in the House of Commons until March 28, and debate was minimal. The Co-operative Commonwealth Federation urged public ownership of pipelines, but that was the only significant dissent, and the bill passed easily on a voice vote. Curiously, there was no mention in the debate of the eventual Great Lakes route to Sarnia; the bill simply enabled international connections and exports. The IPL bill was not considered until the final three days of the session because required notices first had to be published in Newfoundland newspapers.

Imperial Oil’s ownership was reduced to about 50 per cent after the initial IPL share issue in September 1949, which raised the $90 million (equivalent to $990 million today) needed for construction. Other investors included oil companies, institutions, and the general public. Imperial’s holding was further diluted to 33 per cent in later issues, but it remained the largest shareholder until 1983. Imperial’s purchasing department also continued to act as IPL’s agent, for a fee, and all purchase orders bore the Esso logo until 1978.

With government approval and financing in place, IPL moved into high gear. The entire route was surveyed in the summer of 1949, and company agents began negotiating right-of-way with 2,100 landowners in Canada. Lakehead Pipe Line Company, incorporated that summer, would have to deal with its surveying and 400 landowners during the winter. The engineering team relocated from Tulsa to Edmonton and Superior in November 1949, and laid the first pipe from the ice across the South Saskatchewan River near Regina a few months later. Their American leader quit after a month of Edmonton winter, and Roger Clute became chief engineer, a title he would hold for the next 20 years. Everything was in place for the three contractor groups and their 1,500 workers who would undertake what was then the world’s largest single-season pipe-laying project during the wet, muddy spring and summer of 1950.

(Calgary writer Robert Bott was commissioned in the late 1980s to write a corporate history of IPL, Mileposts: The Story of the World’s Longest Petroleum Pipeline, which was distributed to employees on the 40th anniversary of incorporation in 1989. He conducted 46 in-depth interviews with key figures in the company’s evolution and toured many locations along the line from Edmonton to Sarnia. He has continued to write about energy and pipelines, including major projects for the National Energy Board, and received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Petroleum History Society).