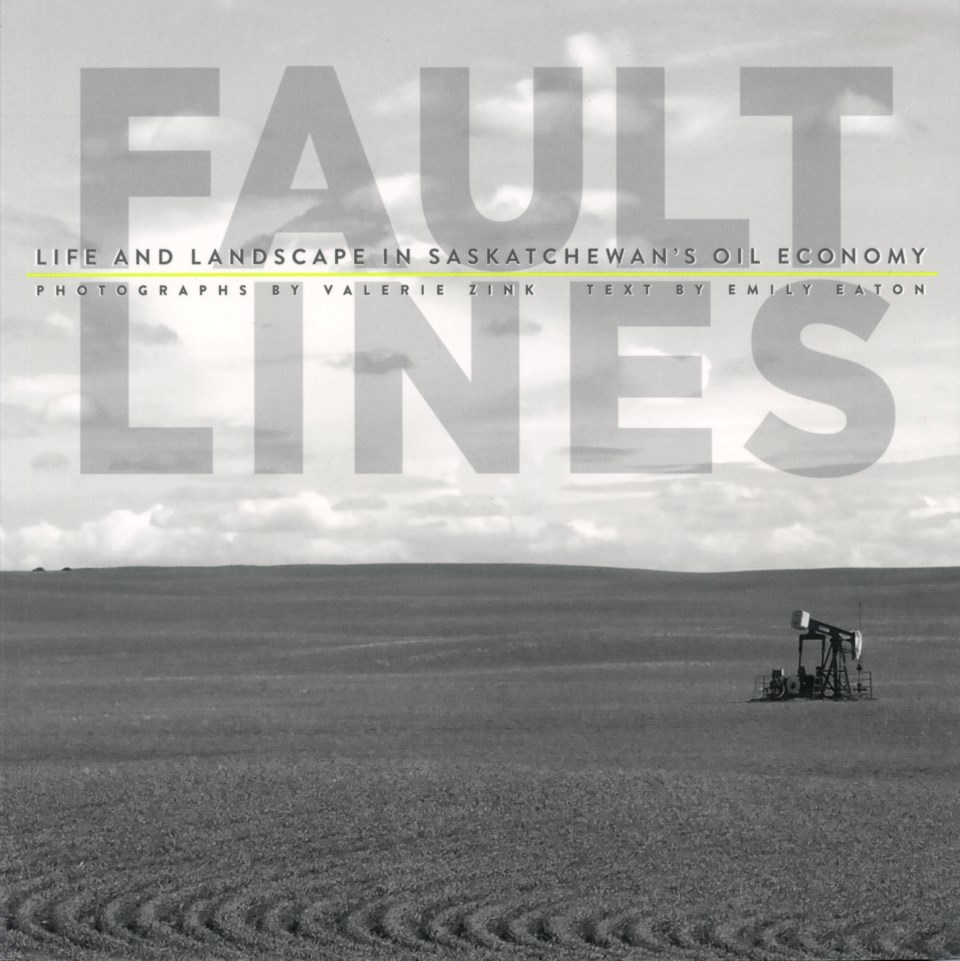

Back in 2014, University of Regina associate professor of geography Dr. Emily Eaton and photographer Valerie Zink set out on a summer tour of Saskatchewan’s oil producing regions, talking to people impacted by the petroleum industry. At that time, the pair spoke with Pipeline Newsin Estevan about their project. On Oct. 18, 2016, their book, Fault Lines: Life and Landscape in Saskatchewan’s Oil Economy, was released.

Published by the University of Manitoba Press, the 108-page book was sent to Pipeline News for review prior to launch. Much of it is composed of high-contrast black and white pictures. It starts out with a helpful map outlining not only the oil pools of the province, but also the rural municipalities they visited in each of the oil-producing regions. And this map might be the first time you will find the boundaries of Saskatchewan’s various numbered treaties with First Nations overlaid with oil pools.

Dark images

In a preface, photographer Zink writes, “As wood-crib grain elevators are torn down, pumpjacks are taking their pace as the new fixture of the prairie landscape. Amid the ravages of rural decline, promises of prosperity during the recent oil boom breathed new life into old constructs of the Last Best West, spurring a wave of migration and minting millionaires in towns with skyrocketing rents and overstressed infrastructure. From the sea-can motel on the outskirts of Estevan to seismic testing sites on Thunderchild First Nation’s Sundance grounds, this series of 77 images captured during the height of the boom considers the ways in which the oil economy is remaking the spatial and cultural landscape rural Saskatchewan. More than a lament for a pastoral plains, these images testify to a moment of transition and urge viewers to consider the complex consequences of rural communities’ engagement with the oil economy.”

While there are some smiles in Zink’s photos, through high-contrast editing and purposeful dark exposure in many cases, most present a feeling of melancholy and bleakness. Of particular note: several businesses portrayed, including Estevan’s Derrick Motor Hotel, Baba’s Bistro and Ron’s the Work Wear Store (Estevan location), have closed since the pair did their tour in 2014, when oil was still US$100 per barrel. ATCO Estevan Lodge had closed just before the tour.

The essays

Although rarely directly attributed to their sources, the text is based on more than 70 interviews throughout the province for 2011 to 2015. The interviews included oil workers, regulators, environmental consultants, landowning farmers and ranchers, community pasture staff, Indigenous land defenders, municipal politicians, temporary foreign workers and social service providers.

Eaton’s essays cover five chapters: The Past, Present and Future of Oil in Saskatchewan; Hosting the Oil Industry; Working the Oil industry; Servicing the Boom, and Resisting the Oil Industry.

In Hosting the Oil Industry, she describes the distinction and separation of surface versus mineral rights, explaining, “The perception that landowners are getting rich from hosting infrastructure is largely false: by the definition of the Act, they are being compensated for the last agricultural use of their lands … For families trying to resist farm consolidation and corporatization, oil lease income, though meant only to compensate for last agricultural use, can be the difference between selling the farm and staying on the land.”

She adds, “Unlike surface rights owners, private mineral rights owners are compensated handsomely through annual payments of oil royalties that provide them with substantial ongoing income that more than accounts for the nuisance of surface leases. Thus, in any given landowning community, a complicated landscape of oil interests structures farmer’s and rancher’s relationships to the industry.”

Therein Eaton sets up one of the numerous conflicts suggested in the book: the dichotomy between the surface rights owners, who get most of the hassle; and mineral rights owners, who get most of the money. (This applies in the 25 per cent of the oil producing regions where mineral rights are free-hold and not held by the Crown.)

The book pulls no punches referring to the uglier side of the business, from the effects of vented and leaking hydrogen sulphide on those living nearby, to careless field operators who leave gates open, allowing cattle out, to animals being killed by pumpjacks. Saline produced water spills are highlighted. Eaton writes, “In fact, in many ways the oil industry is more accurately in the business of waste management, given that they must properly dispose of the water that accounts for 75 to 95 per cent of each barrel extracted. The sheer volume of ‘produced water’ that companies must dispose of at their own cost means the potential for spills is significant.”

She added, “While spilled oil will biodegrade over time, salt is a persistent contaminant.”

Through several examples throughout the book, Eaton frequently refers to people’s self-censorship of criticizing the industry, as either they, their family or neighbours are often dependent on it for some or all of their income.

In Working the Oil Industry, Eaton focuses on the male-dominated, contract-based feast and famine nature of the business, one that takes a hard toll on families.

Eaton highlights the difficulties of living in an oil-fueled boomtown in Servicing the Boom. From overpriced, short-supply housing, to temporary foreign workers who toiling in fast food restaurants for just above minimum wage, she discusses the strains put on communities when times are booming.

It’s in her Resisting the Oil Industry chapter where Eaton’s true feelings are hinted at, as she highlights protests at Thunderchild First Nation and an area north of La Loche. It is worth noting that Eaton has made something of a second profession as a frequent protester for various causes. While not at all mentioned in its pages, during the time this book came together, she has been involved with protests on a broad number of topics. Her favourite causes include numerous aboriginal issues; pro-Palestinian (she visited Palestine recently); boycott, divest and sanctions against Israel; pro-renewable energy; anti-pipelines; and that is not an exhaustive list, either. Her Facebook page is populated with frequent postings about her presence at numerous protests.

She is occasionally one of the organizers. We reported she was the speaker at a February 2015 Saskatoon meeting that hoped to drum up support for banning fracking in Saskatchewan.

In her conclusion, Eaton touches on the downturn that has gripped the industry over the last two years. Due to the publication timetable, there was substantial lag between much of the book’s writing and final printing, thus, the downturn’s tremendous impacts are all-but-missing from this book.

She writes, “The recent downturn, although certainly painful for oil-producing regions, also opens up opportunities to articulate a different future. The burden is on all of us to bring to live alternatives that can break the cycle of boom and bust and that are more environmentally and socially just.”

It is important to note that Pipeline News was consulted several times with regards to the research for this book, where we largely spoke of the positives of the industry. This included that aforementioned meeting with Eaton and Zink in Estevan during their 2014 tour. Despite this, CBC was quoted three times in the footnotes section, and Pipeline News was not footnoted once. Yet, in a Facebook post on July 27 regarding the Husky oil spill, she wrote, “Pipeline News is a very pro-industry rag, but it's always got the most complete coverage of SK's oil industry. Here is the most detailed coverage I've seen of the spill - Including the size of the pipe - 16 inches, the source of the oil - Husky's Paradise Hill site (north of the river) and details about the incident report.”

Eaton’s writing and Zink’s photos lay out the Saskatchewan oil industry, warts and all. The first few pages focus on the benefits of the oil industry, and occasionally, begrudgingly, benefits pop up throughout the remainder of the pages. The rest of the book focuses primarily on the warts. If you work in the Saskatchewan oil patch, buy this book. But you aren’t going to like it.